Acceleration in Python: Which Is Right for Your Project?

Published August 17, 2021

Dale Tovar

Quansight recently assisted the University of Oxford on the sgkit library, a new genetics toolkit. Sgkit is based on the scikit-allel project, which has moved into maintenance mode. Part of the impetus behind this large rewrite was to (1) allow for larger genomics datasets, (2) enable GPU support, and (3) transition to a more sustainable, community-maintained project. Sgkit is meant to improve upon scikit-allel and one of the most important improvements lies in how the computationally intensive code is written. Indeed, a key consideration for any scientific Python library is how to structure the algorithmic code around the slow Python interpreter. We'll return to sgkit below.

Fast computation in Python relies on compiled code. Under the hoods of popular scientific computing libraries like NumPy, SciPy, and PyTorch are algorithms and data structures implemented in compiled languages. By using multiple languages, the aforementioned libraries and many others are able to run interactively in Python, but with the benefits of fast compiled code, facilitating real-time data analysis and manipulation. While this combination is highly desirable, reaping the benefits of both interactivity and speed, there are many ways to achieve this combination and the ways that developers have gone about this task have changed over the years. In this post, I'll highlight three main ways that open-source developers have approached writing performant Python libraries.

- Using multiple languages in the same module

- Writing the codebase in a compiled language and writing bindings to other languages

- Using a Python-accelerating library

Why Does Python Need Speeding Up in the First Place?

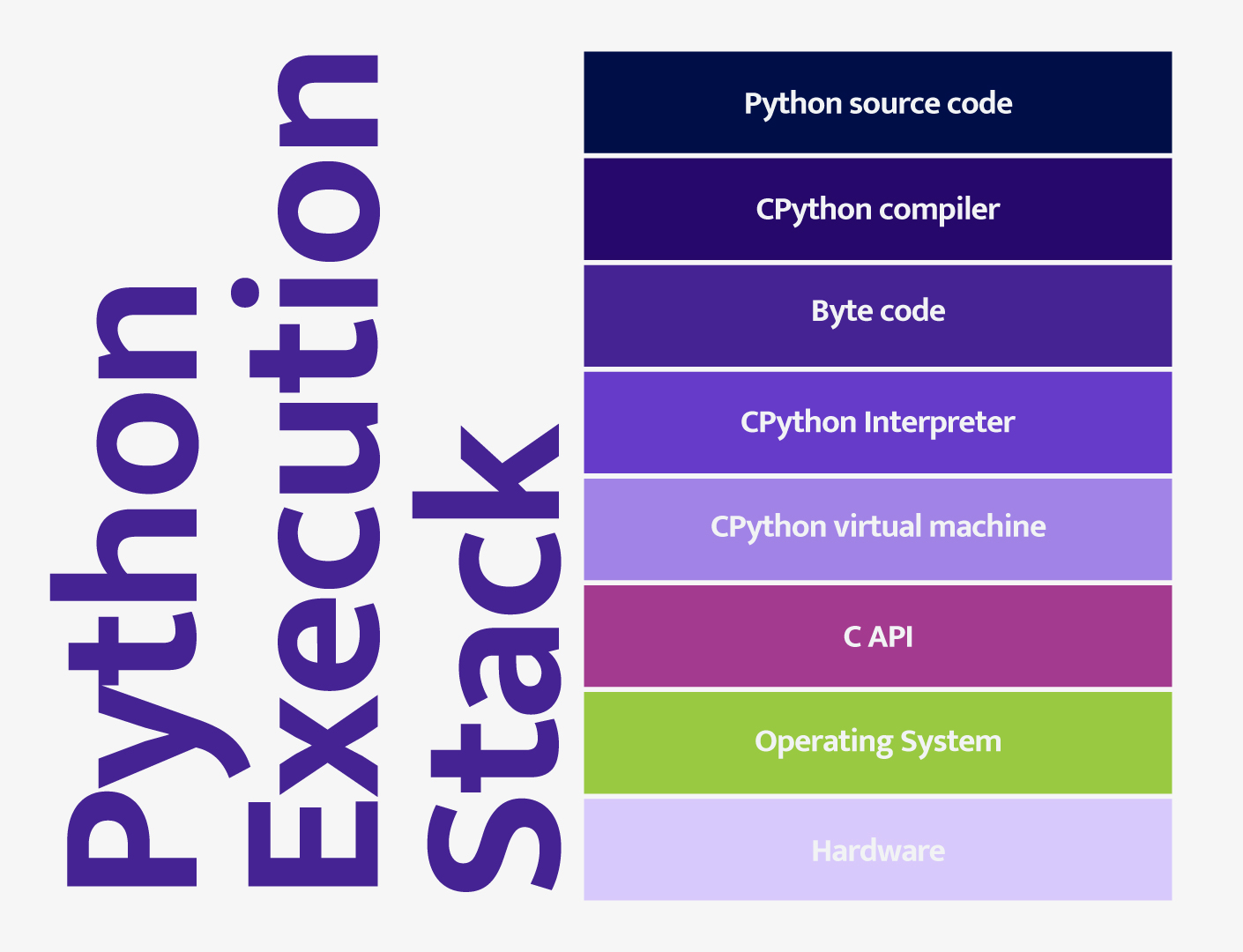

Some of the same qualities that make Python user-friendly and good for data science are the same qualities that make Python slow. The main reason is that Python is an interpreted language. Most Python runs using the following model:

Python source code is passed to the CPython compiler which generates Python byte code. The byte code is then passed to the interpreter. The main bottleneck in this process is the Python interpreter. As a result, code written natively in Python tends to run much slower than similar code code written in a compiled language like C or Fortran. Fortunately, we can compile compute-intensive operations in another language (often C or C++) as a library that extends the Python virtual machine. In this way, we can call these operations directly in the Python source code but bypass the slow interpreter, resulting in improved performance.

Option 1: Multiple Languages in the Same Module

A common strategy, especially among older libraries, is to write computationally

intensive algorithms in C or C++ and call the algorithms from the outward-facing

Python code. NumPy is a good example of this type of organization. Much of the

key ndarray internals are written in C. Likewise, some of the algorithms for

ndarray operations are written in C—see the implementation of the

Timsort algorithm inside NumPy.

[Editor's note: This implementation has since been converted to C++.]

Similarly to NumPy, many of the important routines inside scipy.sparse

including indexing and matrix multiplication are written in C++. This kind of

approach works well for writing performant code. It does come with some

downsides, however:

- Contributors will need to know C/C++/Fortran to be able to make changes to the compute-intensive code.

- The language barrier may prevent many Python developers from contributing.

- Libraries following this model cannot easily be ported to other languages.

Regarding this last point, while it is 'easy' to write bindings for a pure C/C++ library, it is not so easy to do so for a Python library. For example, NumPy and DyND are both fast array libraries in Python. DyND is written purely in C++ with Python bindings in a separate repository. A developer need only write bindings to the C++ library for DyND to be used in R, Julia, or most any other language. This is not the case with NumPy. To use NumPy from another language would require reimplementing it entirely in that language and maintaining it separately.

While this approach will result in fast code, the above points should be considered when beginning a project.

Option 2: Writing the Codebase in a Compiled Language and Writing Bindings to Other Languages

An increasingly common approach today is to write the core of your library in C or C++ and write bindings to more data science-friendly languages like R, Julia, and Python. Writing a self-contained repository or module in C++ where all of your algorithmic code goes affords multiple benefits:

- Your code may reach more users across different languages.

- Other developers can write bindings for whatever language they prefer since most all languages can interface with C++.

- Algorithmic changes/developments are centralized and only need occur in a single place.

Of course, this strategy is not without shortcomings as well:

- Anyone who wants to make substantive changes to the library must know how to code in C++.

- Since most users of scientific computing libraries don't know C++, contributions from your main user base may be scarce.

- Without a large contributing base it can be difficult to keep the steam going on an open source project.

These are important points to consider when you begin organizing your project. This kind of organization is especially common among BLAS implementations and math libraries more generally. There are many good examples of this strategy. One of my favorites is the Tensor Algebra Compiler (TACO).

TACO

For sparse tensors, which contain mostly zeros, there are many ways to

efficiently store and manipulate them. See my previous post on sparsity for more details. (Editor's note: This post

is pending migration.) There are formats like COO, DOK,

CSF, among numerous others including many that are unique to matrices. A

cost of having many different formats is that developers have to write

customized algorithms for performing operations like elementwise addition and

matrix and tensor multiply between many different sparse tensor formats. TACO

generates these kernels automatically. The user can specify the operation and

formats of the tensors they are using and TACO will generate optimized code to

perform this operation. TACO is written in C++. If we look at the

TACO repository, we can see that there are Python bindings in the

same repo. Unlike the example of scipy.sparse in the previous section, the C++

code in TACO stands on its own and is fully self-contained. TACO can be used

from Python, but it does not rely on Python to function. If anyone were

interested in using TACO in a different language, since all of TACO is pure C++

they need only write bindings.

To note: One of the easiest ways to write bindings for Python from C++ code is to use pybind11.

Option 3: Using a Python-Accelerating Library

With tools such as Pythran, Cython, and Numba it is now easier than ever to write performant code solely in Python. All of these tools allow you to transform native Python code into compiled code. This comes with several clear advantages:

- Codebases in a single language tend to be easier to write/maintain.

- Libraries written in pure Python are easier to build/package.

- There is no language barrier for community contribution.

- Good compatability with NumPy and other libraries including GPU support in some cases.

- All of the above tools are pretty easy to get working.

I can think of a couple of disadvantages to this approach though:

- Any pure Python library cannot be easily ported to any other langauge. (All work for a similar package in R or Julia would have to be duplicated and separately maintained.)

- These tools may require altering one's code to work properly, sometimes significantly.

This approach has become very common in recent years: Most of the algorithmic code inside scikit-learn is written with Cython, there is Pythran and Cython code in SciPy, and Numba is used extensively in pydata/sparse.

A Quick Note About SciPy

SciPy is a very complicated project. It includes aspects of all three of the above approaches: algorithmic C++ code, bindings to fast linear algebra libraries, and algorithms written with Pythran and Cython. Consequently, SciPy benefits and suffers from many of the advantages and disadvantages of each approach and is challenging to maintain. It does, however, demonstrate well the many ways one may go about organizing Python packages.

Scikit-allel and Sgkit

Returning to where we started, let's have a look at scikit-allel and its successor, sgkit. Scikit-allel offers both domain-specific data structures and algorithms written in Cython to operate on those data structures. The many data structures do, however, pose a few issues: (1) having many data structures introduces a large maintenance burden and (2) not all of the data structures scale well to large datasets. Sgkit improves on these shortcomings.

Sgkit uses a single data structure in the form of an

xarray.Dataset with specific attributes. This decision

affords a high degree of flexibility regarding how the computations take place.

The array objects in an xarray.Dataset could be standard Numpy arrays, GPU

arrays using CuPy, compressed arrays using Zarr, or sparse

arrays using pydata/sparse. Using Dask with Xarray is

compatible with all of the aforementioned options as well. The algorithms in

sgkit are written using Numba, offering support for both CPU- and GPU-based

computation. Also, the algorithms are written with Dask in mind to address

issues of scaling. These differences between scikit-allel and sgkit are shown

below:

- Data structures

- Scikit-allel uses many data structures

- Sgkit uses one data structure

- Algorithms

- Scikit-allel uses Cython to accelerate algorithmic code

- Sgkit uses Numba to accelerate algorithmic code and enable GPU-based computation

- Parallelism

- Scikit-allel uses different data structures for single- versus multi-node processing

- Sgkit uses a single data structure, which can scale to whatever compute resources are available

In this post I have focused mainly on three different strategies for structuring algorithmic code in a scientific Python library and the pros and cons of each. Sgkit is an example of how scaling and compute resource management can factor into organizing algorithmic code. This example also highlights other considerations such as whether to structure a library around a single data structure or many.

Conclusion

As you can see, there are many ways to organize a software library. Each approach offers its own pros and cons and are appropriate for different kinds of libraries. In my opinion, the second and third approaches are more favorable as they may be easier to build and maintain and may reach a wider developer and user base.